Main Menu - Misc. - Clothing/Textiles - Medieval Wales - Names - Other Medieval - Publications - Harpy Publications

copyright © 2001, 2004, all rights reserved

(This article was originally published in Tournaments Illuminated #137 (Winter 2001). The current version has additional commentary based on subsequent discussions with other researchers)

A 13th century linen tunic, associated with Saint Louis, is preserved in the treasury of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. It is unusual for linen garments to survive from medieval Europe except for those that have been preserved due to their association with saints. Other examples from the 11-13th century include albs associated with Saint Thomas Becket at Sens (France) and Santa Maria Maggiore (Rome, Italy), one associated with Saint Bernulf at Utrecht (Netherlands), one associated with Saint Hugh at La Valsainte (Switzerland), and several whose connections I have not yet been able to identify in Munich, Assisi, and Rome. Of these, the Saint Louis garment is by far the simplest in design and construction and seems more likely to represent an ordinary everyday undergarment as contrasted with the elaborate ceremonial vestments that several of the others clearly represent.

The Saint Louis garment was described briefly and diagrammed by Dorothy K. Burnham in her booklet Cut My Cote (Royal Ontario Museum, 1973, reprinted 1997). Her diagram (including a suggested cutting layout, as well as a diagram of the garment put together) has been reproduced in other sources familiar to historic costumers, including Crowfoot, Pritchard, and Staniland's Textiles and Clothing c. 1150-1450 (HMSO, London, 1992) and as far as I have been able to determine, no other study of this garment has been published. (If one has, I would be eager to hear of it.)

The tunic cut, as Burnham presents it, is a very simple design, with a single rectangular panel forming the front and back (no shoulder seams), trapezoidal sleeves set into the body panel with a very slight shaping to that panel where they are attached, and gussets, formed from the triangular pieces cut off to shape the sleeves, set into the center front and back skirt in pairs. Her diagram shows a narrow band edging the rounded-triangular neck opening and crossing in an X at the base of the front (where the opening comes to a point). A similar tape is shown forming an X at the top of the central gusset. She estimates the width of the fabric (which forms the width of the body panel and the top width of the sleeve pieces) as approximately 22 inches or 56 cm.

Burnham mentions in her brief notes that "it was not possible to make a proper examination" of the garment, I would assume this was due to the conditions of its display. I had the opportunity to examine the garment visually (behind glass) while in Paris recently and the current display makes it possible to add to Burnham's information and, in some cases, suggest modifications to it.

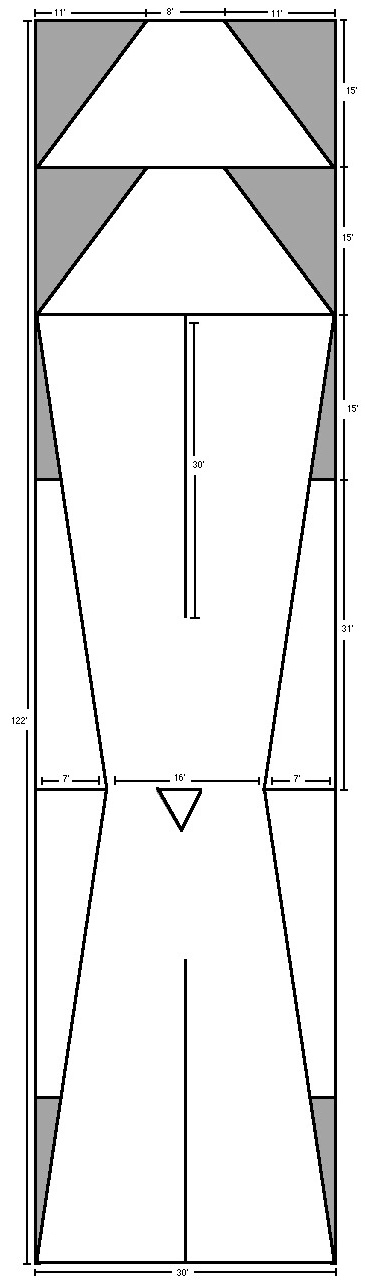

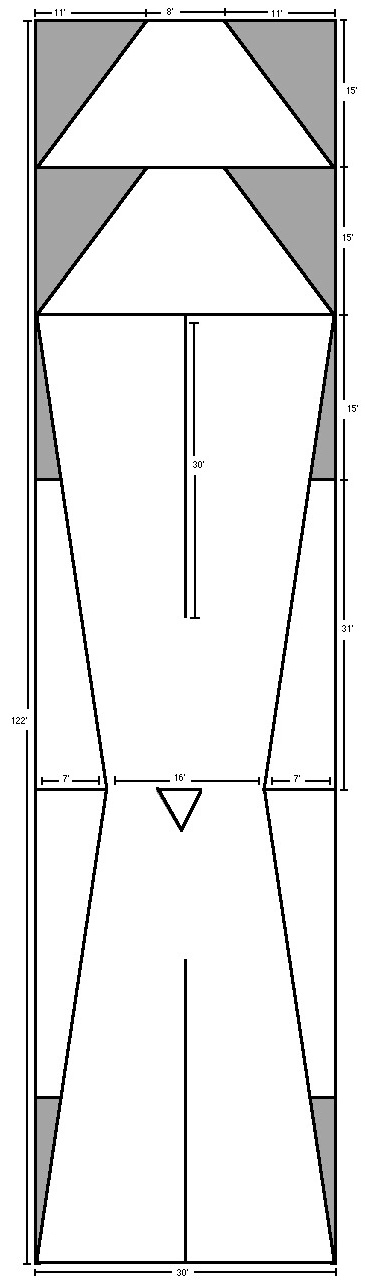

The major differences I observed from Burnham's diagram is that the sleeves are shorter and more sharply tapered, being wider at the base and slightly narrower at the wrist. (Having previously made a copy of the garment based on Burnham's diagram, this difference in dimensions struck me immediately, even before I started making measurements.) The body-panel itself is tapered, rather than rectangular. (This can be seen by tracing a vertical thread from the base of the armscye to the hem: it fell approximately 4" from the side-seam at the hem.) The central gusset is taller than in Burnham's layout, making it more reasonable for it to have been produced from off-cuts of the body taper rather than the sleeve taper. My observations agree roughly with Burnham's diagram in the overall length of the garment, the width at the shoulders and at the base of the armscye, and in having the largest width of the sleeve pieces essentially identical to the largest width of the body piece. In the case of my interpretation, this fabric width would be about 30" rather than Burnham's 22". Other than the difference in sleeve proportions, my proposed cut is slightly fuller in the skirts than Burnham's. A possible cut based on my observations is shown in figure 1. A comparison of the results of the two cuts is shown in figure 2 (my version in black lines, Burnham's in gray), although I have omitted the slight shaping of the armscye from Burnham's version.

fig. 1

fig. 2

It isn't clear to me whether this armscye shaping is present. The overall dimensions of the pieces as I measured them suggest a straight, overall taper, but no special shaping at the arm. Burnham's cut is more efficient of the proposed fabric than mine, as the off-cuts of the sleeve taper are left over in my cut. These off-cuts could, however, be the source of the tape for the seam-finish (see below).

I was also able to observe some details of construction that Burnham omits (probably due to lack of interest).

The garment is made of a relatively fine linen, approximately equivalent in weight to what is sold currently under the name "handkerchief linen", but somewhat more closely woven than that. The weave is a fairly balanced tabby and there are occasional slubs in both the warp and weft. (There were no clues visible to the direction of the warp in any of the pieces.) The visible stitching is all very fine.

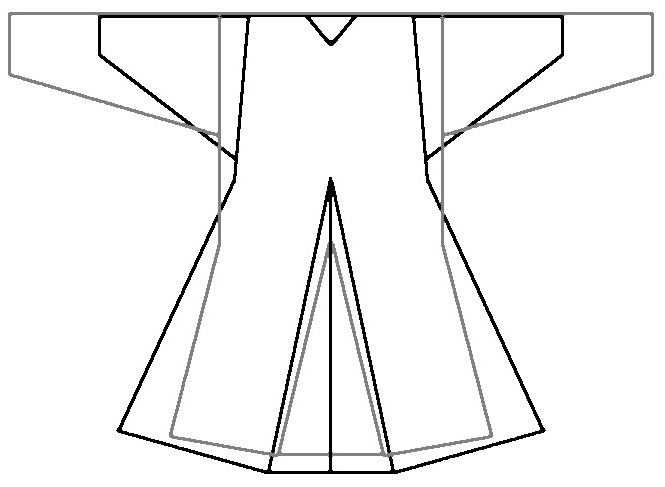

The tape that Burnham shows in her diagram at the neck and the top of the gusset actually represents a seam finish that is present on all the visible seams of the garment. At all places where it is visible, this seam-finish is cut on the straight grain of the fabric. In addition to the neck edge, it is present on the seam attaching the sleeves to the body, on the lengthwise sleeve seam, on the side seams of the body, and on all seams involved in the central gussets. The X formed at the top of the gusset is not a separate application, but simply the ends of this seam finish, continuing past the point of intersection. Based on the way the seam finish crosses and extends past the seam at the gusset top (or the edge at the center front of the neck), it is clearly a separate tape, applied over the raw edges of the seam and sewn down on both sides (rather than being a flat-felled seam). This tape is much narrower than Burnham's diagram suggests -- the finished width is about 2-3 mm, and the fabric used must have been about twice that before the edges were folded under. (See figure 3 for a cross-section view of the probable construction.) The top of the gusset is slightly gathered for a couple of centimeters, rather than being entirely flat.

fig. 3

The wrist and hem edges have a small rolled hem about the same width as the seam finish (i.e., 2-3 mm). This is rolled to the "outside" of the garment as displayed, and the seam finishes are also "outside" as displayed. I strongly suspect that the garment is being displayed inside-out and that these features should actually fall on the inside of the garment, but it's hard to complain about the display since the details would be impossible to examine otherwise!

As a result of the above article being published, I've been in correspondence with several other people who have examined the garment under similar conditions (i.e., as museum visitors, nose pressed to the glass, but not having more direct access). With their kind permission, I here present some of their commentary and images.

Stephen Bloch and Deborah Peters, based on a visit in the summer of 2002 write:

"By and large we found the thing to agree with your article -- except for one crucial feature.

The armscyes, it seemed to us, were quite clearly curved and angled: at the top, they were cut approximately on the grain (perhaps even angled inward a tad), while at the bottom they were at almost a 45-degree angle to it. I remembered you saying something about following grain lines, although I didn't remember what measurements you came up with, so I did the same -- not only from the bottom of the armscye to the hem, but from top to bottom of the armscye. The former measurement came out 3-4" (which, I now see on re-reading your article, matches your result), but the latter is recorded in my diary as 4-6"! This is decidedly more angled (and, as mentioned above, curved) than even Burnham says.

If my measurements are correct, the garment is at least 8" wider at the midsection than at the shoulder. (Which happens to be the discrepancy between your width measurement and Burnham's... coincedence?) Unfortunately, I was a ninny and didn't measure the total width of the garment at top, bottom, OR middle.

I haven't yet tried making a shirt based on this interpretation, but it obviously leads to a very different cutting diagram and a very different fit."

I clarified that he was sure that the armscye horizontal differential was, indeed, 4-6" plus the 3-4" differential between the bottom of the armscye and the hem. This makes for a significant difference in body shape. Since neither of us had directly measured the hem width (which would have been impractical, as the garment is hanging in folds), then assuming my shoulder measurement is correct, the garment is 6-8" wider on each panel just under the arms, as well as that much wider at the hem.

"I'm pretty sure the armscye seams are flat-felled: they seemed to be fairly flat on one side, and bulgy on the other. The bottom hem has the same look, so I assume it's a rolled hem (rather than, say, tape over a raw edge, which would look the same on both sides). The neck hem looks rolled, too, if you don't happen to look at where it continues into an X on the chest (which seems thoroughly inconsistent with a rolled hem, and consistent with your interpretation)."

Here I have to comment that, given that the neck hem looks rolled except at the X where we can tell it's not, this opens up the question of whether the hem and sleeve wrists are, indeed, rolled, and not similarly finished with a tape! Stephen's questions also pointed out a place where my description had been unclear. The tape finish on the neck edge isn't folded over the edge of the farbric (e.g., similarly to a double-fold bias binding edge would be treated), but is sewn right-sides-together, folded to the wrong side, raw edge folded under, then sewn down. For a diagram, see the Archaeological Sewing article. (Ignore the fact that the diagram is in the "wool" section. Also, the version here lacks the top-stitching seen in the sewing article.)

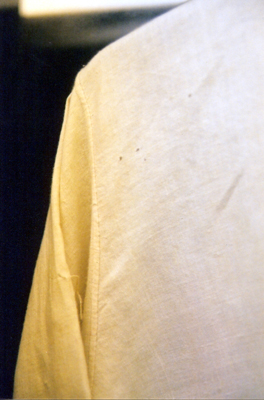

The following images were taken by Stephen Bloch who has kindly given me permission to reproduce them. He retains all rights to the images and should be contacted directly for further information on their use. Click on the thumbnail for the full sized image. Click on the word "enhanced" for a Photoshopped version that enhances the contrast of the details (but completely screws up the color values).

The left sleeve as displayed (right as worn)is the complete one. The image shows the startling narrowness of the seam. Also visible here is the relationship of the upper part of the armscye to the grain of the fabric.

Left sleeve  enhanced

enhanced

The right sleeve as displayed (left as worn) is torn off, but the seam is still preserved. This gives us a convenient view of what the seam looks like from both the inside and outside of the garment.

right sleeve  enhanced

enhanced

The neck opening shows the tape finish of the edge and the X crossing at the center front. Depending on your browser settings, the full-size image of the neck opening should be approximately life size, so it will give you a better idea of how frighteningly narrow the seam finish is!

neck  enhanced

enhanced

Taking Stephen's observations about the extra cut-out of the armscye and adding them to my measurements, we get modifications of figures 1 and 2 as follow.

**insert new figures here**

This site belongs to Heather Rose Jones. Contact me regarding anything beyond personal, individual use of this material.

Unless otherwise noted, all contents are copyright by Heather Rose Jones, all rights reserved.