Main Menu - Misc. - Clothing/Textiles - Medieval Wales - Names - Other Medieval - Publications - Harpy Publications

This material appeared in slightly different form previously as a class handout. Permission is explicitly given for the use of my versions of these embroidery patterns for personal, non-commercial use. Permission is explicitly withheld for the use of my patterns in the creation of commercial merchandise.

The purpose of this presentation is not simply to say, “Here’s some Viking embroidery you can do,” but to show what the actual data and artifacts are on which these interpretations are based. I’m a firm believer that needlework -- indeed, any type of craft work -- needs to be understood in the larger context in which it existed. I also think it’s important to know the difference between what we know (the tattered fragments) and how people may use that knowledge (e.g., the “King Canute” reconstruction).

The technical drawings from the 1869 article by Worsaae are, by my understanding, out of copyright and have been included here. I have included re-drawings of the photographs from Hald of pieces not included in Worsaae, as well as my own pattern drawings that are composites from all the sources. The reconstructions commissioned by the National Museum of Denmark for the "King Canute" costume are very impressive and can be seen in Iverson and Jørgensen but are not included here for copyright reasons.

This material comes from a burial at Bjerringhøj, in Mammen parish, Middelsom herred, in northern Denmark. The site includes a chamber grave with a stave-built coffin and a wide variety of grave goods, and has been dated to the end of the 10th century. (The metalwork style of this site has given its name to an entire genre of motifs.)

The textile remains were damaged somewhat by amateur handling during the original excavation, and some of the original observations can no longer be duplicated. In addition to clothing fragments, the site included a down-filled cushion with decorative stitching on the seams, a variety of tablet-woven trims, remnants of fur associated with the textiles, and several pieces of imported silk.

The embroidery is probably the largest collection of Viking-era sewn-thread decoration. (Decorative wire and metal decorations of clothing can also be found, especially at Birka.) All the embroidery appears to be associated with a single garment, tentatively identified by the original finders as a cloak. The ground fabric is a very fine (20-24 threads per cm), 2:1 twill, dark brown (naturally colored) wool and the embroidery is also in wool in a variety of colors. Original reports indicate that there were also gold paillettes associated with the embroidered fabric, according to one description, "on the breast in the shape of a cross", but current opinion associates these with the ends of the supposed cloak-ties rather than with the embroidered sections.

The embroidery is done in stem stitch, outlining the motifs and sometimes filling them as well, with the filling either following the lines of the outline, or in some cases adding internal texture (as in the paired deer/lions). Some parts of the motifs are not filled in. Usually, the outline is in a different and lighter color than the filling.

Chemical analysis of the textiles identifies an indigotin blue (this could theoretically be from woad or indigo, but I believe woad is much more plausible at this date); a madder red, another madder-like red but probably not madder itself, and undyed (white). (Some of the silks from the grave were dyed purple with lichen, but none of the wools show evidence of this color.) The National Museum of Denmark reconstruction of the embroidery uses white, a light and dark indigo-blue, and three brownish shades ranging from gold to a medium orangey-brown to a dark reddish-brown. In the descriptions below, I identify the color-patterns visible in the photographs, and then give the museum reconstructions of the patterns separately. (The standardized patterns use the museum reconstruction color-patterns.)

All of the embroidered motifs are fragmentary, with some more recoverable than others. The identified motifs include:

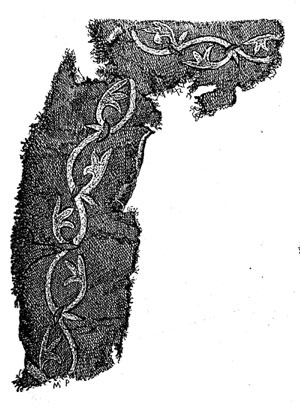

A relatively narrow band of curving vines and three-lobed leaves. These motifs are entirely filled in. The photographs show a very pale (white?) outline, medium tones filling in the leaves, and a darker color for the "bars" at the base of the leaves. The museum reconstruction has dark blue "bars", a white outline elsewhere, leaves and vines filled with gold, with the "extra leaf" (see the diagram) alternating between light blue, gold, and orange.

Technical drawing from Worsaae; tracing by me. (There is also a photograph of the piece in Hald.)

There is a magnified detail of one of these motifs in Iversen et al. showing both the right and wrong sides of the work. It clearly shows the stem-stitch technique and the way the lines of stitching follow the outlines of the motif with a lighter outline one stitch wide around the edges.

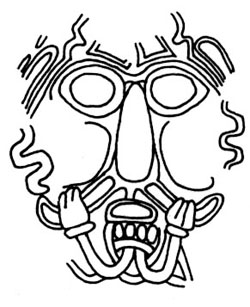

A relatively narrow band of outline-only faces, with filled-in three-lobed leaves in pairs between each set of faces. The photographs show only that the face outlines are dark and the leaves are possibly variable medium tones. The museum reconstruction uses dark blue outlines for the faces and has pairs of leaves sequentially in white, gold, and orange (or possibly these three and red-brown as well).

Ttechnical drawing from Worsaae; tracing by me. (There is a photograph of the same piece in Hald.)

The rear end of spotted, long-tailed beast, done primarily in outline, except for a stripe along the belly that is filled in. The photograph shows medium tones except for a pale belly-stripe and "ankle" blocks. The color detail photo shows that the belly-stripe is filled with an alternation of blue and some pale color. The museum reconstruction uses dark blue outlines and spots, gold "ankle" blocks, belly stripe, and tail-tuft, white teeth, and a gold or orange tongue and pupil (the eye has a dark blue outer ring). Note that the tail-tuft and front end of the animal are entirely missing from the original and have been reinvented for the reconstruction.

See figures above. There is a color close-up of the stripe along the belly in Iversen et al. showing white outlines filled with blue.

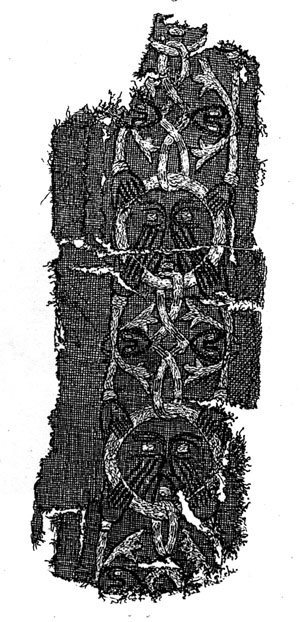

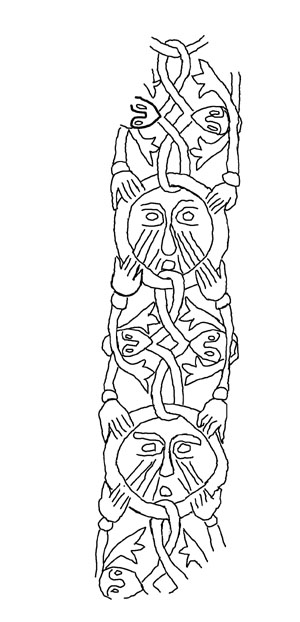

A wider band of faces, each formed by a filled ring surrounding an eye-and nose motif done in outline, with the rings joined by interlaced strapwork with simple acanthus vines emerging from pairs of smaller face-masks and terminating in hands that grasp the ring around the face, all filled in. (This won't make sense without looking at the diagram.)

Photographs and a painting made at the time of original discovery show the face details and the hands as very dark (blue-black) the pupils and mouths of the larger faces as pale, the large rings as very pale (white?), the acanthus vines with a pale outline and a medium-pale filling, and the strapwork with a pale outline and alternating bands of pale and medium color filling them.

The museum reconstruction has the ring around the large faces white, with the facial details dark blue except that the pupils and mouths are white. The small faces are also dark blue, also with white pupils. The hands are dark blue and in outline only with a white oval as the base. The acanthus vines have a white outline with a gold filling, and the strapwork has a white outline with alternating blocks of gold and orange filling.

Technical drawing from Worsaae; tracing by me. Hald has a black and white photo of the entire piece and Iversen et al. has a color photo of a single repeat of the motif and a color re-drawing of the entire piece.

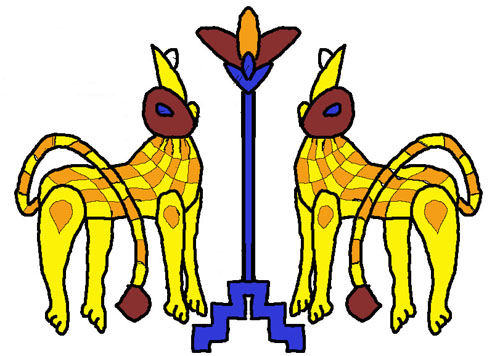

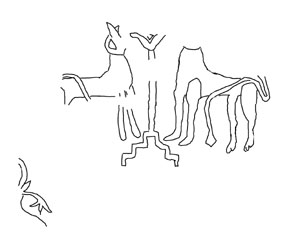

A tree-like motif emerging from a stepped base, done in outline except for some fragmentary foliage at the top, between a pair of facing animals variously interpreted as "deer" or "lions"; they have long narrow legs, long tufted tails, but the heads are both fragmentary and don't help much in identification. The animals are entirely filled in, and the pattern of the fill adds contours of the legs against the body. There are no color photos of the original and the lighting on the photographs makes it difficult to distinguish shades. The only shade distinction visible in the original drawings appears to be a dark eye-ring, with the rest of the embroidery being an indistinguishable medium tone.

The museum reconstruction gives the tree a dark blue base, trunk-outline, and leaf-base, with orange filling for the trunk. The three leaves are outlined in gold, with the central leaf filled with orange and the outer two filled with red brown. The beasts have red-brown heads and tail-tufts, and are otherwise outlined in white, including white outlines of the upper part of the near limbs and around three "toes" on each foot. The legs and snout are gold, with orange upside-down teardrops on the upper part of the limb. The tails and bodies are filled with alternating blocks of orange and gold. The "lower jaw" is white.

Technical drawing from Worsaae; tracing by me. There is also a black and white photo in Hald.

Several extremely fragmentary motifs that appear to be birds, done in outline only. There are three bird-like heads, and the lower part of a body and feet. The colors are light to medium in poor black and white photographs. These are not visible as part of the museum reconstruction. There is another, very damaged, piece that Iversen et al. identifies as “quadrupeds”, but much of the pattern must be reconstructed from needle-holes alone and I have not included it here.

Redrawn by me from Hald.

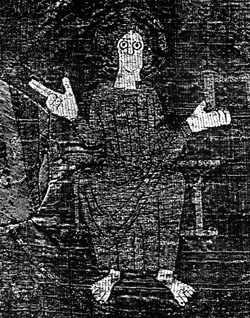

Although, as noted above, the Mammen site gave its name to a style of metal decoration found there, the embroidery motifs are largely unrelated in style to the strapwork and interlaced-beast styles of art found in wood and metal there. Instead, there seems to be an emphasis on "foreign" inspirations. The tree-and-surrounding-beasts motif is extremely reminiscent of designs found on Near Eastern and Byzantine silk textiles of the era and earlier.

Tree & beasts motifs from textiles of the Mediterranean region, both before and after the date of the Mammen burial.

The acanthus-style foliage is identical to that found commonly in manuscript and other art on the continent from Classical times on, and continuing in popularity through the high medieval period throughout Europe.

Acanthus motif from an 11th century Visigothic manuscript

![]()

The birds and leopard are more naturalistic in style (if crudely executed) than the typical zoomorphic motifs in contemporary Scandinavian metalwork. Only the style of the mask-faces seems to connect with characteristically Scandinavian motifs. Particularly characteristic is the forming of the eyes and nose with a single looping line (rather like the "eye" for a "hook-and-eye" set). Very similar motifs can be seen on a piece of horse equipment from the Mammen grave, and in the "St. Ewald" embroidery from 9-12th century Germany. The continuity of many of these styles can be seen as late as the early 13th century in a German embroidery showing the same style of facial features and English embroideries showing the same acanthus vine pattern and some fragmentary felines that are actually the closest stylistic match for the Mammen leopard that can be found.

Mask and grasping hands motif from horse harness found in the Mammen grave; similar facial features on the “St. Ewald” embroidery (German ca. 9-12th c.); early 13th century embroidery from Brunswick - note similar facial style

Early 13th century English embroideries from a bishop’s tomb with acanthus and with stylized lion/leopard figures

The original site report suggests that the embroideries were all on a single garment which appears to have been a cloak. The surviving fragments give no real evidence to their placement, and in some cases show partial bands of decoration ending abruptly and oriented relatively haphazardly with respect to other motifs on the same piece. There is also at least some evidence that the embroidered cloth may be a re-use of some other object. The edge of the cloth where the leopard’s tail is cut off is bound with a separate edging of fabric.

The National Museum of Denmark commissioned reproductions of (reconstructions of) these embroideries and associated garments in the context of creating a speculative set of clothing appropriate for King Canute, based on an illustration in an 11th century manuscript, as well as on archaeological material. The gorgeousness of this set of reconstructed garments distracts somewhat from the fact that they do not accurately reproduce the layout and application of the archaeological material. Motifs have been moved, rearranged, and shared out over more than one garment. In the "Canute" garments, the small faces are used in a ring draping around the neck opening, lying as if it were a long necklace. The leopard is placed on the upper sleeve and the paired beasts and tree are placed in the center back. The large face band is placed along the front edges of a short semi-circular cloak and the acanthus band is placed along the hem of the cloak.

Keep in mind if you look at pictures of this project that the idea was not to create a reproduction of garments form the Mammen grave, but rather to apply information from those garments to an entirely different project. While the reconstructed garments supply inspiration for how these embroideries could be used (and are based on other representations of clothing decoration), they do not represent the actual layout of the Mammen garment.

Given the uniqueness of the Mammen find, there is very little basis for confidence in extrapolating how and where embroideries of this type might be used. Manuscript illustrations and embroidered figures show bands of decoration that suggest the placement of tablet-woven brocades, but are less useful for the possible placement of free embroidery. The most similar surviving pieces close in time include semi-circular mantles with scattered or structurally arranged motifs, such as the German (but possibly Byzantine in origin) "star cloak" of Henry II (early 11th century). A piece more similar in concept, in being free embroidery applied directly to the ground fabric, is the tunic of Saint Bathilde, in 7th century France. (The embroidery is in the form of a series of necklaces with pendant cross and medallions.) But these comparisons primarily point out the general lack of context for free embroidery on clothing (especially secular clothing) in this period.

Hald, Margrethe. 1980. Ancient Danish Textiles from Bogs and Burials. National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen. ISBN 87-480-0312-3

Iversen, Mette et al. 1991. Mammen: Grav, kunst og samfund i vikingetid. Jysk Arkaeologisk Selskab, Hojbjerg. ISBN 87-7288-571-8

Jørgensen, Lise Bender. 1992. "I Knud den Stores klae'r" in Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark, Kobenhavn.

Worsaae, I.I.A.. 1869. "Om Mammen-Fundet" in Aarboger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie. 1869:203-218.

Color Keys for Patterns (not to scale) - click on image for full-size version in separate window.

The patterns in the separate images are scaled to the size of the original embroidery. Click on image for full-sized version in separate window.

This site belongs to Heather Rose Jones. Contact me regarding anything beyond personal, individual use of this material.

Unless otherwise noted, all contents are copyright by Heather Rose Jones, all rights reserved.