Main Menu - Misc. - Clothing/Textiles - Medieval Wales - Names - Other Medieval - Publications - Harpy Publications

This essay is one of a planned series on topics of interest to historic novelists writing lesbian characters and relationships.

This article is one in a continuing series on topics and motifs of use to people creating historically-grounded characters that resonate with modern lesbians. That description is very carefully circuitous. The particular combination of attitudes, beliefs, priorities, and behaviors associated with a modern lesbian identity were not combined in the same ways historically and often had different meanings for people of an earlier era. The same is true, of course, of the attitudes, beliefs, priorities, and behaviors associated with a modern heterosexual identity, but people generally don’t feel the need for disclaimers on straight history. In this article, I frequently use the word “lesbian” as a shorthand for “women who have sex with women” or as a translation for historic terms in other languages. This is primarily to avoid cumbersome phrasing and isn’t meant to imply anything about the self-identification of the women so labeled. One additional disclaimer I want to emphasize is that although my interest here is filtered through a lesbian lens, many of the items covered here could also be understood in a transsexual context, either in terms of how the historic figures understood their own lives or in terms of how modern people “use” that history. I don’t mean to erase this angle, but it’s not how I’m approaching the topic.

My underlying purpose here is primarily as a creator of fictional historic characters, and for that reason my research draws not only on factual historic accounts, but on historic literature, on art, and on the invented mythology of the age that described what people thought they knew about sexual activity between women, whether or not the specific activities ever happened. To some extent, I’m interested in the study of possibilities: what could people of the middle ages and renaissance envision women doing together and how did they understand those possibilities in context?

To dispense with some basic definitions, the content of this study is physical activity between two individuals who are both biologically female, where that activity is explicitly sexual or erotic in nature, regardless of how the participants in -- and the recorders of -- this activity understood it. Furthermore, I specifically include non-genital activity where the same actions, if indulged in by a mixed-sex couple, would be understood as unmistakably sexual or erotic in nature. This last touches on a Catch-22 prevalent in medieval attitudes toward sex between women. This attitude held that if the activity involved some version of penetrative intercourse, then it was heterosexual in nature and one of the participants must be functioning as a man. But if the activity didn’t involve penetrative intercourse, it could be excluded from the category of “sexual activity”. Under this framing, there was no such thing as sex between women because if it was sex, one of them wasn’t really a woman, and if they were both really women, whatever they were doing wasn’t really sex. We’ll see this paradox played out in the intense (and somewhat prurient) interest medieval writers had in the use of “diabolical instruments to excite desire”, i.e., dildos (although that specific word doesn’t occur in the literature covered here).

It’s inescapable, given the nature of historic records, that both what information was recorded, and what was preserved and transmitted down the ages, leans heavily toward negative and judgmental treatments of sex between women. Some of the most detailed records are from legal prosecutions where either the sexual activity itself or other behaviors associated with it (such as cross-dressing) were treated as illegal and could even result in execution as a punishment. In a context such as this, both the confessions of the accused and the testimony of their sexual partners can’t be treated as neutral and objective. Similarly, the warnings and prohibitions that were designed to prevent sexual activity in all-female religious communities, while they provide useful information on what behaviors were considered sexual or as “gateway” activities to sexuality, are inherently negative.

So with many large grains of salt, let us start in Classical times and work our way onward. The Classical era isn’t part of the primary focus of my interest, but it lays the groundwork for later attitudes.

There's a common perception that classical Greek culture was a haven of sexual diversity and tolerance. But with few exceptions -- and the reputation of the poet Sappho notwithstanding -- the male domination of recorded culture leaves us only a few neutral references for lesbian activity. These frame sexual orientation as inborn, as in Plato's myth of humans originally having double bodies and seeking their literal "other halves" in love, or the story of a drunken Prometheus moulding humans out of clay and mixing up the sexual organs when he attached them. Plato's label of "heteiristriai" for women who “do not pay attention to men but are attracted to other women” [Hallett 1997] gives no clue to sexual activity, but Phaedres's version of the Prometheus story identifies the women as "tribades", from a root meaning "to rub" -- a semantic field that gave rise to a number of other similar labels such as the Latin "fricatrix" and a cluster of Arabic terms discussed later. Another version of the Prometheus story also implies oral sex, claiming that the mix-up of sexual organs had resulted in the women's tongues being formed from penises [Hallett 1997].

A similar treatment of lesbian sexual activity as inherent is found in Greek and Roman astrological texts of the 1st and 2nd centuries. They identify the astral conditions under which a woman will be sexually transgressive as a lesbian who “[does] in women the act of men”, or in which a women will take an active sexual role with women, even referring to their partners as wives. This falls in what will be an extensive theme of distinguishing an "active" participant who is seen as being a male analog, where her "passive" partner is not necessarily categorized as deviant. The astrological genre continued as late as a 7th c. text that distinguishes the stellar conditions under which a woman becomes a “crissatrix” or “thruster” as opposed to a “fricatrix” or “rubber”. [Brooten 1996]

Roman references to sex between women played on three themes: masculinization of the "active" partner, anachronism (characterizing lesbian activity as occurring in a more decadent past), or Hellenization (portraying the activity as Greek in origin, or using Greek vocabulary to describe it even when equivalent Latin terms were available). [Brooten 1996] This last is only a special case of a long tradition of exoticizing lesbian activity or attributing it to foreign cultures.

The framing of lesbian sex as Greek or exotic most typically took the form of vocabulary choice, identifying women as tribades, rather than the Latin equivalent fricatrixes. But drama played on this stereotype as well, as in a play by Plautus that alluded to unspecified sexual intercourse between an Athenian courtesan and her female slave [Brooten 1996], a motif repeated in a later comedy by Truculentus [Hallett 1997].

Examples of masculinization include a fictitious legal case recorded by Seneca the Elder of a man who caught his wife in bed with another woman engaging in tribadry and killed them, after first ascertaining whether the "man" in the act was "natural or sewed-on". [Brooten 1996, Hallett 1997]

This fascination with strap-ons is sometimes merely implicit in vocabulary, as in an epigram by Martial who describes a woman as a “fututor” (fucker) of women who “dares to join two cunts together.” [Brooten 1996, Hallett 1997] Sometimes it is more overt as in a mockingly sympathetic argument in a 4th century satire responding to arguments in praise of sex between men. A character responds that one should then “bestow the same privilege upon women, and let them have intercourse with each other just as men do. Let them strap to themselves cunningly contrived instruments of licentiousness, those mysterious monstrosities devoid of seed, and let woman lie with woman as does man.” [Brooten 1996]

Perhaps the ultimate example of masculinization is Ovid’s story of the love of Iphis and Ianthe, where the social need to have one partner “play the man” has divine resolution when Iphis is physically transformed into one. [Brooten 1996] But as this moves the pair out of the category of sex between women, it doesn’t belong here.

Even when women are described in masculine terms, not all the associated sexual activity is penetrative. Martial describes an athletic woman as literally sexually voracious, “devouring girls’ middles”, in an allusion to oral sex. [Brooten 1996, Hallett 1997] The possibility of cunnilingus is presented in its denial by a character of Juvenal who upholds the purity of Roman women, claiming that, “Tidea does not lick Cluvia, nor Flora Catulla.” [Brooten 1996] And Lucian’s colorful character Megilla, described as married to one courtesan and, with her, seducing a third woman by kissing her “like men”, nonetheless denies either having or needing a penis analog, saying “I don’t need it at all. You’ll find I have a much pleasanter method of my own,” though the specifics are left to the imagination. [Brooten 1996]

Some erotic behavior between women falls more on the borderline of the category, as when the writer Alkiphron describes courtesans at a women-only party “performing sensuous dances for one another, wiggling and shaking their hips, buttocks, thighs, and bellies and judging each others beauty in the process.” [Brooten 1996]

Before plunging into the dreariness of early Christian penitential manuals, let’s pause a moment to consider an anecdote from the early Irish Book of Leinster. The topic is a king’s mystical test of truth-telling, but it plays out in the context of a woman who turns up pregnant but swears that she hasn’t had sex with a man for many years. The king jumps to an unexpected conclusion, asking “Have you had playful mating with another woman? And do not conceal it if you have.” She admits to this, and the king explains, “That woman had mated with a man just before, and the semen which he left with her, she put it into your womb in the tumbling, so that it was begotten in your womb.” To the extent that such a pregnancy would be possible (as opposed to many of the clearly impossible things occurring in early Irish tales), this would imply activity involving contact between the two vulvas. [Bitel 1996, Bernhardt-House]

It’s entirely too glib to claim that legal prohibitions are proof of the activity being prohibited, but they can certainly be taken as proof that someone imagined the activity in question. And the early Christian penitential manuals and rules for women’s religious communities provide examples of what sorts of potentially erotic activities it was felt necessary to discourage. Specifics are often lacking. Augustine of Hippo exhorted nuns to avoid “those things which are practiced by immodest women, even with other females, in shameful jesting and playing” [Brown 1989, Murray 1996] and suggested that if they went to the public baths they should go in groups of three or more (presumably to avoid being in unsupervised pairs in a place where sexual activity was suspected). [Brooten 1996] Some of the prohibited behaviors were probably viewed as “gateway” activities rather than sexual, per se, as when Donatus forbade nuns to “take the hand of another or call one another ‘little girl’ or take the hand of another for delight.” [Murray 1996] Most religious rules prohibited sharing a bed or sleeping naked together. But should these rules fail, the penitential manuals provided penances for “a woman who practices vice with a woman” [Benkov 2001, Matter 1989], or “who joins herself to another woman after the manner of fornication,” although the punishments for these activities were fairly light. More serious punishment was reserved for activity that touched on male prerogatives, as when the activity used “an instrument”. [Murray 1996, Matter 1989] Or as Hincmar of Rheims describes in more detail:

Quae carnem ad carnem non autem genitale carnis membrum intra carnem alterius, factura prohibente naturae, mittunt, sed naturalem huiusce parties corporae usum in eum usum qui est contra naturam communtant: quae dicantur quasdam machinas diabolicae opeationis nihilominus ad exaestuandam libidem operari.

“They do not put flesh to flesh in the sense of the genital organ of one within the body of the other, since nature precludes this, but they do transform the use of the member in question into an unnatural one, in that they are reported to use certain instruments of diabolical operation to excite desire.” [Murray 1996, Matter 1989]

These vague and dreary prohibitions must suffice us for several centuries of evidence, enlivened only in the 10th century by what may be the earliest known use of the term “lesbian” unambiguously to refer to sexual relations between women, in texts by the Byzantine writer Arethas. [Bennett 2000]

The Islamic world around the turn of the millennium has a reputation for relatively progressive ideas, though the day-to-day reality must have depended greatly on individual circumstances. There are traces in the early medieval Arabic literary tradition of at least a dozen romance tales featuring female couples, most notably the story set in the 7th century of Hind Bint al-Nu`man and Hind Bint al-Khuss al-Iyadiyyah, known as al-Zarqa’ whom legend identified as the first lesbian couple. [Amer 2009, Crompton 1997 This story focuses primarily on the love and devotion between the two women but other texts are more forthcoming.

Some Arabic authors such as the 9th century al-Kindi reported a medicalized view of lesbianism as a sort of itch in the labia, which could only be treated by friction and a resulting orgasm. For complex humoral reasons, only sex with another woman would effect the cure. [Amer 2009]

The 12th c Spanish Moslem writer Sharif al-Idrisi, then at the Sicilian court of Roger II, records a passage that, like earlier astrological treatises, treats lesbian behavior as an inborn orientation, and like most writers of the day views it as masculinization, but gives the whole a refreshingly positive spin. [Murray 1996, Murray 1997]

“There are also women who are more intelligent than the others. They possess many of the ways of men so that they resemble them even in their movements, the manner in which they talk, and their voice. Such women would like to be the active partner, and they would like to be superior to the man who makes this possible for them. Such a woman does not shame herself, either, if she seduces whom she desires. If she has no inclination, he cannot force her to make love. This makes it difficult for her to submit to the wishes of men and brings her to lesbian love. Most of the women with these characteristics are to be found among the educated and elegant women, the scribes, Koran readers, and female scholars.”

As in Greek and Latin, the standard terminology in Classical Arabic for female same-sex partners, based on the root “sahhaqu”, carries a meaning of rubbing or grinding indicating the type of activity implied. [Murray 1997]

Meanwhile, back in Christian Europe, we begin seeing more literary references to sexual activities between women, including an unusually unselfconscious description in a Latin poem lamenting the longing of one woman for her absent "singular rose", preserved in a collection at Tegernsee, in which the writer reminisces “I recall the kisses you gave me, and how with tender words you caressed my little breasts”. [Matter 1989]

G. unice sue rose, |

To G., her singular rose, From A. -- the bonds of precious love. What is my strength, that I should bear it, That I should have patience in your absence? Is my strength the strength of stones, That I should await your return? I, who grieve ceaselessly day and night Like someone who has lost a hand or a foot? Everything pleasant and delightful Without you seems like mud underfoot. I shed tears as I used to smile, And my heart is never glad. When I recall the kisses you gave me, And how with tender words you caressed my little breasts, I want to die Because I cannot see you. What can I, so wretched, do? Where can I, so miserable, turn? If only my body could be entrusted to the earth Until your longed-for return; Or if passage could be granted me as it was to Habakkuk, So that I might come there just once To gaze on my beloved’s face-- Then I should not care if it were the hour of death itself. For no one has been born in to the world So lovely and full of grace, Or who so honestly And with such deep affection loves me. I shall therefore not cease to grieve Until I deserved to see you again. Well has a wise man said that it is a great sorrow for a man to be without that Without which he cannot live. As long as the world stands You shall never be removed from the core of my being. What more can I say? Come home, sweet love! Prolong your trip no longer; Know that I can bear your absence no longer. Farewell. Remember me. |

|---|

The Abbess Hildegard of Bingen, also in the 12th century, illustrates the confusing tangle of attitudes towards women's passions for each other, both emotional and physical. We have a number of documents describing Hildegard's efforts to secure the return of one of her former nuns, Richildis,who had been appointed to head a different institution against Hildegard's will. The written record clearly indicates that Hildegard had a deep emotional attachment to the woman mingled with a significant amount of possessiveness and desire for her physical presence, but in other writings she condemns sexual activity between women at least when one overtly imitates a male. This attitude is shown by a character in one of her plays, who asserts, “a woman who takes up devilish ways and plays a male role in coupling with another woman is most vile … and so is she who subjects herself to such a one in this evil deed. For they should have been ashamed of their passion, and instead they impudently usurped a right that was not theirs.” Elsewhere, in her medical and scientific writings, Hildegard sets forth that women “may be moved to pleasure without the touch of a man” (sine tactu viri in delectationem movetur) although this passage doesn’t necessarily indicate interactions between two women as opposed to the simple absence of a man. [Schibanoff 2001]

There was an entire genre of medieval literature seeking to classify and categorize the world. The 12th century Livre des manieres by Etienne de Fougeres is a rather satiric representative of this genre, with his verse providing a long list of colorful metaphoric images for lesbian sex, referring to it as "the beautiful sin" and somewhat unusually emphasizing non-penetrative activities. [Clark 2001, Murray 1996]

| … Ces dames ont trove I jeu: O dos trutennes funt un eu, Sarqueu hurtent contre sarqueu, Sanz focil escoent lor feu … Hors d’aigue peschent au torbout Et n’I quierent point de ribot. N’ont sain de pilete en lo rot Ne en lor branle de pivot. Dus a dus jostent lor tripout Et se eminent plus que le trot; A l’escremie del jambot S’entrepaient vilment l’escot Il ne sunt pas totes d’un moile; L’une s’esteit et l’autre crosle. L’une fet coc et l’autre polle Et chascune meine son rossle. |

… These ladies have made up a game: With two bits of nonsense they make nothing; They bang coffin against coffin, Without a poker stir up their fire. … Out of water they fish for turbot And they have no need for a rod. They don’t bother with a pestle in their mortar Nor a fulcrum for their see-saw. In twos they do their lowlife jousting And they ride to it with all their might; At the game of thigh-fencing They pay most basely each other’s share They’re not all from the same mold: One lies still and the other grinds away. One plays the cock and the other the hen, And each one plays her role. |

|---|

The 13th century gives us one of the few artistic depictions from the medieval era that is clearly intended to portray two women engaging in sexual activity. It appears in a version of the “Bible Moralisée”, a biblical commentary that provided in-depth “explanations” of the underlying lessons of various biblical stories. This image shows two same-sex couples -- one female, one male -- each lying together engaged in clearly erotic behavior, while devils lurk in the background. Commenters have noted that in addition to the overall bodily posture of the two women, the gesture where one holds the other’s chin while kissing her is one traditionally associated with erotic activity. [Murray 1996]

ca. 1220 - Bible Moralisée, Parigi; Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Codex Vindobonensis 2554, fol. 2r

Kissing is an activity that is difficult to classify with certainty as sexual. Mouth-to-mouth kissing was used for a variety of symbolic purposes in the middle ages, indicating friendship, loyalty, or even legal acknowledgment, as well as being an erotic act. To illustrate the difficulties, I include an illustration from a 14th c manuscript of the Roman de la Rose. The textual context is the allegorical figure of "Pleasure" leading two maidens into a dance in which “when they were close together, their lips would touch in such a way that you might have thought they were kissing one another’s faces.” [Sautman & Sheingorn 2001] If we had a scene of a pleasure garden in which a dancing mixed-sex couple kissed, it would be an automatic conclusion that this was an erotic act. This is where my project has the advantage over strict history: the image falls within my scope without needing certain knowledge of how the author or the illustrator intended the act.

Roman de la Rose, ms Valencia, Biblioteca universitaria 387, 7v

Cross-dressing and gender disguise were popular motifs in medieval romances and created a context for brushes with same-sex erotic activity, whether or not the characters involved were both aware of it. To complicate the matter, like Ovid's much earlier story of Iphis and Ianthe, these fictional treatments had the option of resolving society's need to masculinize one of the pair with a literal transformation. Thus, in the 14th century story Tristan de Nanteuil, the character Blanchandine, having disguised herself entirely too well as a man in order to accompany her lover Tristan on adventures, is loved and courted by the noblewoman Clarinde. Believing Tristan to be dead, she finds herself forced to agree to marry Clarinde but successfully delays consummation until a miracle transforms her into a man. However if the story's conventions are accepted as true, it fails to fall within my topic as no sexual activity occurs before the transformation. Further, Blanchandine's erotic feelings are dictated entirely by the form of her body: uninterested in Clarinde before the change, but in love with her afterward, and after the change denying any trace of attraction to poor Tristan who turned out not to be dead after all. [Hotchkiss 1996]

Another story that titillates with the erotic possibilities of disguise but stops short of the full act is the late 13th century Roman de Silence. The title character has lived her life in disguise as a man and becomes the focus of illicit love by the queen of the king she serves as a minstrel. The queen's intended transgression is heterosexual adultery, but technically we have physical activity between two biological women:

“[The queen’s] desire for the harper, who played so sweetly, grew stronger every minute … right away, she embraced him [that is, the disguised Silence] and kissed him and told him, “Now just relax! Kiss me, don’t be shy! I’ll give you two kisses for one. Don’t you think that’s an amazing rate of exchange?” “Yes,” said the youth who was a girl. “So kiss me!” said the queen. Right on her forehead, just below her wimple, Silence gave her one chaste kiss-- for you can be sure he had no intention of kissing her the way she wanted. But the lady, who did not care to be kissed in this manner, gave him five long kisses, exceedingly passionate and very skillful.” [The alternation of pronoun gender is part of the original text.]

The queen's actions with Silence are clearly presented as sexual, due to her belief that she is interacting with a man. [Hotchkiss 1996, Roche-Mahdi 1999]

The ambiguities of both behavior and language make interpretation more subjective in the 13th century French story Escoufle (the kite) in which a young woman named Aelis finds herself unexpectedly abandoned by her boyfriend (who goes chasing off after a kite who has stolen his silk purse and doesn’t return to the story until the very end). Aelis promptly takes up with another young woman Ysabel. “Fair Aelis began thinking that the two of them could well spend the night in one bed together.” The implication is primarily one of friendship and probably of social protection, since Ysabel is an established member of a community while Aelis is a stranger and alone. But as the two start up an embroidery business together, their relationship becomes more physically ambiguous as Aelis “moves closer to her, she kisses her, embraces and hugs her” and Ysabel “tells her that she will accomplish completely her wish, whatever it is.” This is language that, in mixed-sex contexts can indicate either sexual or non-sexual interactions, but the language continuing to describe their relationship is framed strongly in the conventions of romance. Ysabel provides Aelis with “so much solace, so much pleasure” and Aelis “enjoys herself in so many ways.” But at the same time the story focuses on their combined search for Aelis’s missing boyfriend. Aelis encounters two further intimate friendships with women in the story, including the same ambiguously suggestive language about sharing a bed and, in the second case sharing a friendship so close “they are all one body/heart and soul; they no longer remember Guillaume [the boyfriend] … No other woman was ever treated in the way the noble countess did [Aelis]; She kisses her, then let the other young women kiss her. Then she takes her to relax in her bedroom, holding her with her naked hand.” [Amer 2008]

Returning to the results of gender disguise, Yde is another character who gains fame and renown in male disguise as a knight and -- in the way of romances -- is rewarded with the hand of her lord's daughter in marriage. Different versions of the story resolve the dilemma of this same-sex marriage in different ways, but what is of interest here is the period between the wedding and that resolution. [Hotchkiss 1996] In one 14th century version, on the wedding night Yde reveals her true sex to her wife Olive, saying, “Lady, I place myself in your mercy … Know that I am a woman like you … And that I have breasts: Feel them.” This doesn’t continue into further physical interaction but Olive promises to keep the secret, responding, “And I will show you such honor as a woman must show her husband … nor will I ever hold you less dear.” [Amer 2008, Clark 1998]

In an earlier 13th century version of the story, Yde prevaricates rather than revealing herself on the wedding night, claiming illness that prevents full consummation but as the story goes, “with these words Olive was hugged” and Olive agrees to the postponement, noting, “Besides kissing, I don’t mind hugs”. And when Olive’s father asks her “Daughter, how is it to be married?” “Sire,” she said, “the way I like it.” But although Olive had been deeply in love with the “male” Yde -- for the text describes that “Olive had seen [Yde] from the windows [and] her entire body throbbed with pleasure” -- she is unhappy after Yde’s true sex is revealed until a miraculous sex-change solves the problem. [Amer 2008]

Interestingly, we have an extremely parallel plot in the Arabic tale The Story of Qamar al-Zaman and the Princess Boudour, known from a 14th century manuscript of the 1001 Nights but likely one of the original inspirations for Yde and Olive in an earlier version. The princess Boudour disguises herself as a man for social protection when her husband mysteriously disappears, and by various adventures she finds herself at the Isle of Ebony whose king abdicates in her favor and requires her to marry his daughter Hayat al-Nefous. In this story, we are presented with three nights of increasing intimacy after the wedding. The first describes Boudour “entering into” Hayat with language that implies penetrative sex. On the second night “Boudour sat down next to Hayat al-Nefous and kissed her” and on the next night “When Boudour saw Hayat al-Nefous sitting, she sat beside her, carressed her and kissed her between the eyes.” This third night Boudour reveals her true sex to Hayat. “she unveiled the truth about her situation … and she showed her genitals and said to her [I am] a woman who has a vulva and breasts.” After which they “spoke, played, laughed with each other, and slept.” And the next morning Hayat stages a fake proof-of-virginity using chicken blood. The Arabic context provides a different option for resolution of the masquerade than was available to Yde and Olive. Boudour’s missing husband turns up, Boudour reveals her true sex to all concerned, abdicates in favor of her husband, and offers him Hayat as a second wife after which all three live happily ever after. [Amer 2008]

Without more context, it can be difficult to tell whether Arabic society of the time was, in fact, more accepting of sexual activity between women, or whether it was simply more acceptable to write explicitly about it. A 13th century collection of anecdotes by the Tunesian-born al-Tifashi, titled “The Diversion of the Hearts by what is not to be Found in Any Book” contains sexual material of a variety of types (as well as non-sexual anecdotes and entertainments) and in some cases treats lesbian sex apparently neutrally or even positively. But the anecdotes are clearly framed by the male author for a male readership. Here, in addition to the usual term “sahq” used for lesbians, meaning “one who rubs or pounds”, there is discussion of women involved in more of an ongoing subculture, rather than isolated activities, who refer to themselves as “zarifa”, meaning “witty, elegant, or charming”, acting as a recognized codeword. Al-Tifashi incudes a rather startlingly frank and detailed description of lesbian sexual technique. [Amer 2001, Malti-Doublas 2001]

“The tradition between women in the game of love necessitates that the lover places herself above and the beloved underneath--unless the former is too light or the second too developed: and in this case the lighter one places herself underneath and the heavier one on top, because her weight will facilitate the rubbing, and will allow the friction to be more effective. This is how they proceed the one that must stay underneath lies on her back, stretches out one leg and bends the other while leaning slightly to the side, therefore offering her opening (vagina) wide open: meanwhile, the other lodges her bent leg in her groin, puts the lips of her vagina between the lips that are offered for her, and begins to rub the vagina of her companion in an up-and-down, and down-and-up, movement that jerks the whole body. This operation is dubbed “the saffron massage” because this is precisely how one grinds saffron on the cloth when dying it. The operation must focus each time on one lip in particular, the right one, for example, and then the other: the woman will then slightly change position in order to apply better friction to the left lip…and she does not stop acting in this manner until her desires and those of her partner are fulfilled. I assure you that it is absolutely useless to try to press the two lips together at the same time, because the area from which pleasure comes would then not be exposed. Finally, let us note that in this game the two partners may be aided by a little willow oil, scented with musk” [Amer 2001]

Moving into the 15th century, we start finding records of legal actions against women for lesbian practices and other associated social crimes. Despite the clear social opprobrium, the amount of data of this type is far less than that for corresponding male transgressions. Those who have combed the legal records have found not more than a dozen examples from the 15th century -- none earlier: 7 women in Bruges in the 1480s, 2 women charged in Rottweil in 1444, and two cases that are interesting in their detail. [Bennett 2000, Boone 1996, Puff 1997]

In 1405, a law case was brought concerning a 16-year-old married woman named Laurence and another married woman named Jehanne. According to Laurence’s testimony, while they were out walking together Jehanne promised Laurence “If you will be my sweetheart, I will do you much good” and on agreeing because she “thought there was nothing evil in it”, Jeheanne laid her down in a haystack and “climbed on her as a man does on a woman … and began to move her hips and do as a man does to a woman.” The encounter was enjoyable enough for both of them that they met several more times for physical relations, but their eventual break-up was problematic enough to come to the attention of the authorities. [Bennett 2000, Benkov 2001, Murray 1996]

However for sheer soap-opera fascination, there’s the trial of Katherina Hetzeldorfer in 1477 in Speier. Katherina was passing, at least nominally, as a man and had arrived in town with a female companion, initially presented as her “sister” but with whom she eventually confessed to a sexual relationship. Although there were some suspicions regarding this relationship, what brought Katherina to the attention of the law was a serious of sexually aggressive adventures, including offering women money for sex and entering women’s houses at night for the purpose of sexual assault. The trial focused on her transgression of gender boundaries in her appearance, but the testimony includes extensive evidence of her sexual behavior. Some aspects of the testimony must be suspect as her partners must have felt the need to present themselves as victims of a gender hoax rather than as willing participants. Katherina’s original companion testified that Katherina had “deflowered her and had made love to her during two years.” Another woman asserted that Katherina had “grabbed her just like a man” … “with hugging and kissing she behaved exactly like a man with women.” And the most detailed testimony concerned how Katherina used an artificial penis both as gender disguise and as a sexual aid. “She made an instrument with a red piece of leather, at the front filled with cotton, and a wooden stick stuck into it, and made a hole through the wooden stick, put a string through, and tied it round; and therewith she had her roguery with the two women….” Katherina’s repertoire also included manual stimulation, with one partner describing, “she did it at first with one finger, thereafter with two, and then with three, and at last with the piece of wood that she held between her legs as she confessed before.” [Crompton 1980, Puff 2000]

Around the 15th century, classical literature was being rediscovered and translated into vernacular languages including both the legendary history of Sappho and the fragments then available of her work, with its unmistakable erotic focus on women. While many commenters preferred to focus on the Phaon myth which resolved Sappho's problematic sexuality into a tragic heterosexual conclusion, the other content could hardly be ignored. Some writers, like Domitius Calderinus in the later 15th c treated it as merely scandalous, noting, “Erynna was the concubine of Sappho … who it is said she used libidinously … she did not fail to love [her female friends] in the manner of a man, but was with other women a tribade, this is abusing them by rubbing.” And vernacular commentary on Sappho sometimes introduces us to less learned equivalents for the terminology of fricatrices and tribades, as with the direct English equivalent "rubster". [Andreadis 2001]

But some 16th c treatments of Sappho took interesting turns in how they used the symbolism of sex between women. A friend and correspondent of the young John Donne envisioned their two muses as followers of Sappho, writing, “Have mercy on me and my sinfull Muse which rub’d and tickled with thyne could not choose but spend some of her pithe and yield to be one in that chaste and mystic tribadry … their swollen thighs did nimbly weave and with new arms and mouths embrace and kiss.” [Andreadis 2001]

As often was the case, the situation of Sappho in an exotic foreign past was part of a general exoticization and othering of lesbian activity. Sometimes this was a direct reference to pagan Greek myth. In The Anatomy of Melancholy, among other categories of “the tyrannies of love” it lists “those wanton-loined womanlings, Tribadas, that fret each other by turns and fulfill Venus … with their artful secrets.” [Andreadis 2001]

But European descriptions of the exotic East often included a fascination for what women did alone together in harems or Turkish baths. A 1585 English translation of Nicolas de Nicolay’s French travelogue of Turkey, describes women at the baths: “Sometimes they do go 10 or 12 of them together … and do familiarly wash one another … and sometimes become so fervently in love the one of the other as if it were with men, in such sort that perceiving some maiden or woman of excellent beauty they will not cease until they have found means to bathe with them and to handle and grope them every where at their pleasures so full they are of luxuriousness and feminine wantonness. Even as in times past were the Tribades, of the number whereof was Sappho the Lesbian which transferred the love wherewith she pursued a 100 women or maidens upon her only friend Phaon.” [Andreadis 2001]

A similarly exoticising account originally published in Latin in 1589 by Ogier Ghislain de Busbecq reads: “ordinarily the women bathe by themselves, bond and free together, so that you shall many times see young maids exceeding beautiful, gathered from all parts of the world, exposed naked to the view of other women who thereupon fall in love with them, as young men do with us at the sight of virgins.” [Andreadis 2001]

Ottaviano Boy, the Venetian envoy to the Ottoman court reports of the women in the harem, “It is not lawfull for anyone to bring ought in unto them with which they may commit deeds of beastly uncleannesse; so that if they have a will to eate Cucumbers, they are sent in unto them sliced to deprive them of the means of playing the wantons.” though it isn't clear whether he's writing of solitary or mutual activity. [Murray 1997]

The 16th century recapitulates most of the types of evidence we've seen in previous centuries. Law codes are still echoing the penitential manuals, as in a 1507 Bamberg code mentioning “women who have lain with other women”, and a late-century Italian law that still carefully distinguishes penalties for different female sexual transgressions: a woman who “behaves like a man with another woman,” one who simply makes overtures, one who “behaves corruptly with another woman only by rubbing,” or one who "introduces some wooden or glass instrument into the belly of another.” The harshest penalties were reserved for physically imitating the male organ. [Benkov 2001, Brown 1989, Puff 2000]

And the courts continue to record application of these laws, at least in cases where particularly transgressive behavior made it impossible to ignore. A Genevan woman executed in 1568 for fornication, among other crimes, testified that although she knew that heterosexual relations with a married man were sinful, she didn’t know that sexual relations with another woman were. A French case of the 16th century records a woman who married a woman, using an artificial penis for sex. And a Spanish document describes women in prison making artificial male genitalia for sexual purposes, though it isn't clear if this was the offense that landed them there. [Benkov 2001, Murray 1996, Puff 2000]

A German case in 1514 in Mösskirch concerns a servant girl Greta who "did not take any man or young apprentice … but loved the young daughters and went after them … and she also used all the bearings and manners, as if she had a masculine affect.” There was never any mention that she used an instrument, and her activities don't seem to have been popularly condemned, but she was investigated on suspicion of being a hermaphrodite, though doctors determined that she was “a true, proper woman”. (hat sie die jungen döchter geliept, denen nachgangen … auch alle geperden und maieren ob sie als ain mannlichen affect hat … ain wahr, rechts weib gesehen worden.) [Benkov 2001, Puff 2000]

Several Dutch cases can be found, including one in 1606 concerning Maeyken Joosten of Leiden, a married woman with four children, who fell in love with a young woman named Bertelmina Wale. Maeyken courted Bertelmina through letters using a male persona, and then in person, still claiming she was “really” a man. Maeyken left her husband to go to Zeeland and married Bertelmina under the name Abraham Joosten. The case is recorded because Maeyken was on trial for sodomy and Bertelmina testified that she “had sexual contact … in every manner as if she were a man.” [Dekker & van de Pol 1989]

Beginning in this period there are increasing records of women who lived as a married couple with one member passing as a man. A Spanish woman know variously as Elena or Eleno de Desopedes lived as a man and married a woman in the later 16th century, before eventually being discovered, although the couple's sexual activities are not recorded. [Bullough 1996]

Male writers sometimes speculated on the motivations of women's sexual activity with each other. Agnolo Firenzuola’s Ragionamenti amorosi has a female character assert that female same-sex love would be preferable to adultery as the woman doesn’t risk her chastity. [Brown 1989] Presumably this is the same sense of “chaste” as found in Sappho’s “chaste and mystic tribadry.”

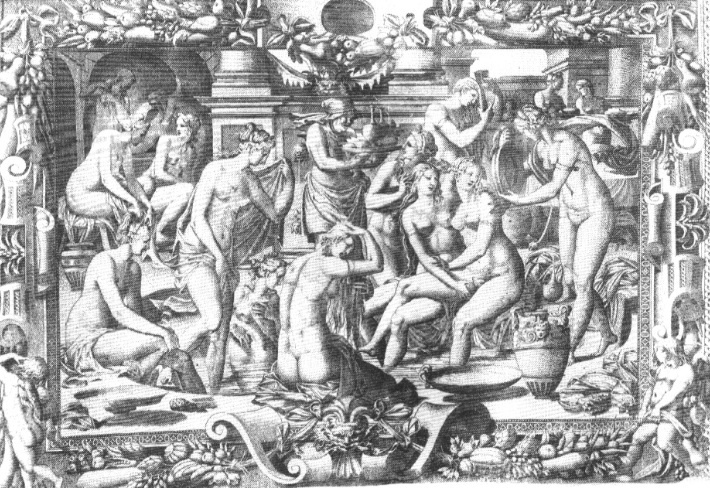

Brantome, whose gossipy writings were meant to titillate, presented lesbian activity simply as an "appetizer" to heterosexual activities, telling a story of a group of “ladies and their (male) lovers” admiring a painting of women at the bath (perhaps quite similar to the one shown below) who were portrayed embracing and fondling each other in so stimulating a way that one lady demanded that her lover take her home to satisfy her immediately. Brantome went into some detail distinguishing activity involving rubbing, with one woman on top of another (in imitation of a man), and the use of an object for penetration (which he seems rather squicked at). But male authors of less racy literature often seemed to be baffled at what two women might do together and wrote their characters with similarly limited imaginations. Sidney's Arcadia describes two amazons going to bed together to discuss their romantic woes with other people who, after getting naked, proceded with “cherishing one another with deare, though chaste embracements; with sweet, though cold kisses.” In the context of the work this activity is presented as not being sexual, per se, despite that it would clearly be viewed as such if the characters' male lovers had been present. [Brown 1989, Faderman 1981]

Jean Mignon “Women Bathing”, Ca. 1550-55 (from Saslow 1999)

Male medical writers of the 16th century had a clinical fascination with the clitoris as a locus of female same-sex sexual activity and begin a long tradition of the mythical “overdeveloped clitoris” as both the cause and enabler of lesbian activity. Fallopius writes, “Avicenna makes mention of a certain member situated in the female genitalia … which sometimes will increase to such a great size that women, while in this condition, have sex with each other just as if they were men. The Greeks call this member clitoris, from which the obscene word clitorize is derived. Our anatomical writers have completely neglected this and do not even have a word for it.” Similarly, Laurentius writes, “I have become aware of the use of this (clitoris) whereby after being rubbed all over it excites the sluggish faculty. It increases in some people to such an inappropriate extent that it hangs outside the fissure the same as a penis; women then often engage in mutual rubbing, such women accordingly called tribades or fricatrices.” [Andreadis 2001

And with this medicalized theme, we'll end with the strange tale of the early 17th century Italian abbess Benedetta Carlini, who was the subject of scandal and official investigation in which her sexual activities with another nun were only a very minor part. Benedetta was, to put it mildly, a very disturbed individual. She had visions and hallucinations. She manifested stigmata which were eventually found to be self-inflicted. She went into trances in which she delivered sermons that included "immodest and lascivious language". She persuaded the authorities at her convent to stage an elaborate ceremony celebrating her marriage to Christ. And after the second time her behavior provoked an extensive investigation by the authorities, she was determined to be a fraud, after which she was imprisoned for the rest of her life.

But of interest here is that, during a period prior to the investigations, when there was concern about her mental state and physical well-being, a nun named Bartolomea was assigned to be her constant companion. It later came out that Benedetta, claiming to be possessed by an angel named Splenditello, repeatedly engaged in sexual activities with Bartolomea, claiming that it was really the angel doing so. [Brown 1986, Matter 1989, Murray 1996]

“For two continuous years, at least three times a week, in the evening after disrobing and going to bed [Benedetta] would wait for her companion to disrobe, and pretending to need her, would call. When Bartolomea would come over, Benedetta would grab her by the arm and throw her by force on the bed. Embracing her, she would put her under herself and kissing her as if she were a man, she would speak words of love to her. And she would stir on top of her so much that both of them corrupted themselves.” Benedetta claimed that the angel Splenditello did these things using her, so it wasn’t a sin. Further investigation brought out additional details. Benedetta would kiss Bartolomea’s breasts, and in addition to the tribadism, there was manual stimulation of the genitals (by both participants) and digital penetration. In addition to their activities in bed, during teaching sessions, Benedetta would use the proximity to touch Bartolomea’s breasts and neck and kiss her while speaking words of love. “Benedetta, in order to have greater pleasure, put her face between the other’s breasts and kissed them, and wanted always to be thus on her…. Also at that time, during the day, pretending to be sick and showing that she had some need, she grabbed her companion’s hand by force, and putting it under herself, she would have her put her finger in her genitals, and holding it there she stirred herself so much that she corrupted herself. And she would kiss her and also by force would put her own hand under her companion and her finger into her genitals and corrupted her…. And while she was doing this she would kiss her. She always appeared to be in a trance while doing this.” Throughout the testimony, Bartolomea emphasized that the activity had been against her will. [Brown 1986]

Despite ending with that somewhat problematic example, I hope this material -- flawed though it is, and hopelessly filtered through the attitudes and paradigms of a sexist and patriarchal age -- serves to illustrate the wide variety of behaviors and models available to pre-modern women in Europe who found themselves, for whatever reason, interested in engaging in sexual activity together.

Amer, Sahar. 2001. “Lesbian Sex and the Military: From the Medieval Arabic Tradition to French Literature” in Same Sex Love and Desire Among Women in the Middle Ages. ed. by Francesca Canadé Sautman & Pamela Sheingorn. Palgrave, New York.

Amer, Sahar. 2008. Crossing Borders: Love Between Women in Medieval French and Arabic Literatures. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

Amer, Sahar. 2009. “Medieval Arab Lesbians and Lesbian-like Women” in Journal of the History of Sexuality: 18(2) 21-236.

Andreadis, Harriette. 2001. Sappho in Early Modern England: Female Same-Sex Literary Erotics 1550-1714. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Benkov, Edith. 2001. “The Erased Lesbian: Sodomy and the Legal Tradition in Medieval Europe” in Same Sex Love and Desire Among Women in the Middle Ages. ed. by Francesca Canadé Sautman & Pamela Sheingorn. Palgrave, New York, 2001.

Bennett, Judith M. 2000. "’Lesbian-Like' and the Social History of Lesbianism" in Journal of the History of Sexuality: 9:1-2; 1-24.

Bernhardt-House, Phillip A. “Middle Irish Lesbian Babymaking: Reading the Niall Frossach Story” (Paper presented at the International Medieval Congress)

Bitel, Lisa M. 1996. Land of Women: Tales of Sex and Gender from Early Ireland. Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

Brooten, Bernadette J. 1997. Love Between Women: Early Christian Responses to Female Homoeroticism. University of Chicago Press.

Brown, Judith C. 1986. Immodest Acts: The Life of a Lesbian Nun in Renaissance Italy. Oxford University Press, New York.

Brown, Judith C. 1989. “Lesbian Sexuality in Medieval and Early Modern Europe” in Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay & Lesbian Past, ed. by Martin Bauml Duberman, Martha Vicinus & George Chauncey, Jr., New American Library, New York.

Bullough, Vern L. & James A. Brundage. 1996. Handbook of Medieval Sexuality. Garland Publishing Inc., New York.

Clark, Robert L. A. 1998. “A Heroine’s Sexual Itinerary: Incest, Transvestism, and Same-Sex Marriage in Yde et Olive’ in Gender Transgressions: Crossing the Normative Barrier in Old French Literature, ed. by Karen J. Taylor. Garland Publishing, Inc., New York.

Clark, Robert L.A. 2001. “Jousting without a Lance: The Condemnation of Female Homoeroticism in the Livre des Manieres” in Same Sex Love and Desire Among Women in the Middle Ages. ed. by Francesca Canadé Sautman & Pamela Sheingorn. Palgrave, New York.

Crompton, Louis. 1997. “Male Love and Islamic Law in Arab Spain” in Islamic Homosexualities - Culture, History, and Literature, ed. by Murray, Stephen O. & Will Rosco. New York University Press, New York.

Dekker, Rudolf M. and van de Pol, Lotte C. 1989. The Tradition of Female Transvestism in Early Modern Europe. London: Macmillan.

Faderman, Lillian. 1981. Surpassing the Love of Men. William Morrow and Company, Inc., New York.

Hallett, Judith P. 1997. “Female Homoeroticism and the Denial of Roman Reality in Latin Literature” in Roman Sexualities, ed. by Judith P. Hallett & Marilyn B. Skinner, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Hotchkiss, Valerie R. 1996. Clothes Make the Man: Female Cross Dressing in Medieval Europe. Garland Publishing, Inc., New York.

Malti-Douglas, Fedwa. 2001. “Tribadism/Lesbianism and the Sexualized Body in Medieval Arabo-Islamic Narratives” in Same Sex Love and Desire Among Women in the Middle Ages. ed. by Francesca Canadé Sautman & Pamela Sheingorn. Palgrave, New York.

Matter, E. Ann. 1989. “My Sister, My Spouse: Woman-Identified Women in Medieval Christianity” in Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, ed. by Judith Plaskow & Carol P. Christ. Harper & Row, San Francisco.

Murray, Jacqueline. 1996. “Twice Marginal and Twice Invisible: Lesbians in the Middle Ages” in Handbook of Medieval Sexuality, ed. by Vern L. Bullough & James A. Brundage, Garland Publishing, Inc., New York.

Murray, Stephen O. 1997. “Woman-Woman Love in Islamic Societies” in Islamic Homosexualities - Culture, History, and Literature, ed. by Murray, Stephen O. & Will Rosco. New York University Press, New York.

Puff, Helmut. 2000. "Female Sodomy: The Trial of Katherina Hetzeldorfer (1477)" in Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies: 30:1, 41-61.

Roche-Mahdi, Sarah. 1999. Silence. Michigan State University Press, Lansing.

Saslow, James M. 1999. Pictures and Passions: A History of Homosexulity in the Visual Arts. Viking Penguin, New York.

Sautman, Francesca Canadé & Pamela Sheingorn, eds. 2001. Same Sex Love and Desire Among Women in the Middle Ages. Palgrave, New York.

Schibanoff, Susan. 2001. “Hildegard of Bingen and Richardis of Stade: The Discourse of Desire” in Same Sex Love and Desire Among Women in the Middle Ages. ed. by Francesca Canadé Sautman & Pamela Sheingorn. Palgrave, New York.

This site belongs to Heather Rose Jones. Contact me regarding anything beyond personal, individual use of this material.

Unless otherwise noted, all contents are copyright by Heather Rose Jones, all rights reserved.